What is Unity?

Tutorial

foundational

+10XP

10 mins

33394

Unity Technologies

In this tutorial, you’ll learn about the Unity engine: why it’s sometimes referred to as a game engine, how it came to be, and how it has evolved over the years.

Languages available:

1. Overview

Unity began its life as a real-time 3D game engine but evolved to be a creative tool that’s used by many different industries. That being said, Unity still retains its game engine roots, and the story of how and why it was created provides insight to why it works the way that it does.

If you’re not sure what the term game engine means, you aren’t alone! Game engines are constantly discussed in the game industry, but are rarely explained — which can be confusing for newcomers and creators in other industries! So let’s begin by first defining what a game engine is.

2. What is a game engine?

The process of creating a game is a great deal more complicated than it appears on the surface. The computer or mobile device on which you’re reading this right now runs an operating system that tells your device how to run power to the screen, keep the brightness setting to where you specified, initiate and maintain access to the Internet, and display text and images on the screen. It’s also doing a lot of tangentially related work in the background, like regulating device access to its power source. That’s a lot to manage, just to display some text!

Now think about creating content rather than just reading or viewing it. If you’ve ever written an email, you know that you personally don’t need to understand the inner workings of your email program in order to write a message. All of that other stuff is handled on your behalf, and you only need to focus on creating the content of your message. A game engine is exactly the same.

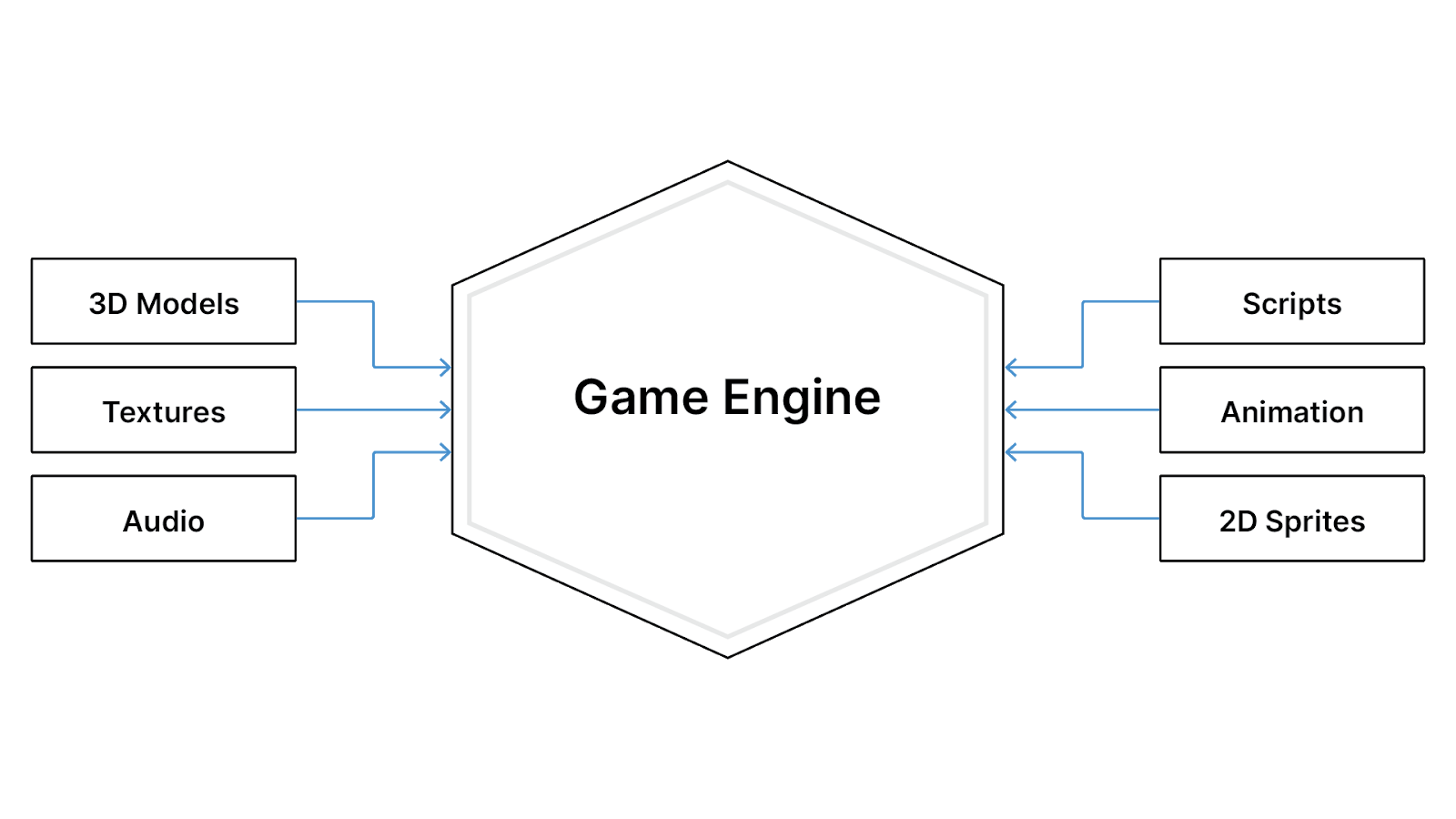

A game engine is the point of convergence for all aspects of creating a game. Games, like all applications, are made of smaller pieces like 3D models, scripts, and audio files. When put together, they create the full user experience. If 3D models, scripts, and audio files were ingredients, Unity (and other game engines) would be the stockpot you dropped them into!

Like the operating system that’s ensuring you’re able to read this tutorial, game engines make sure that your game will display on the screen, objects will be able to interact with other objects, sounds will be audible, and your application will be publishable in a format that your device can run. You provide the content, and the game engine provides the tools to implement it in an environment that will just work.

3. What do you do in a game engine?

Now that you have a basic idea of what a game engine is, let’s learn more about what creators do with it. If a game engine is used to implement the content you bring into it — what is that content?

In a game engine, the creator is putting together everything that the user will experience in the final product. If that product is a game, the creator designs gameplay such as jumping on platforms; if it is an animation, the creator devises the action being recorded; if it is a VR architectural visualization, the creator builds a photorealistic environment that the user will walk through. The game engine also gives the creator a means to make their product into an interactive experience for the user. There’s a great deal more that Unity is doing behind the scenes so that you, the creator, only need to focus on the all-important user experience.

4. What don’t you do in a game engine?

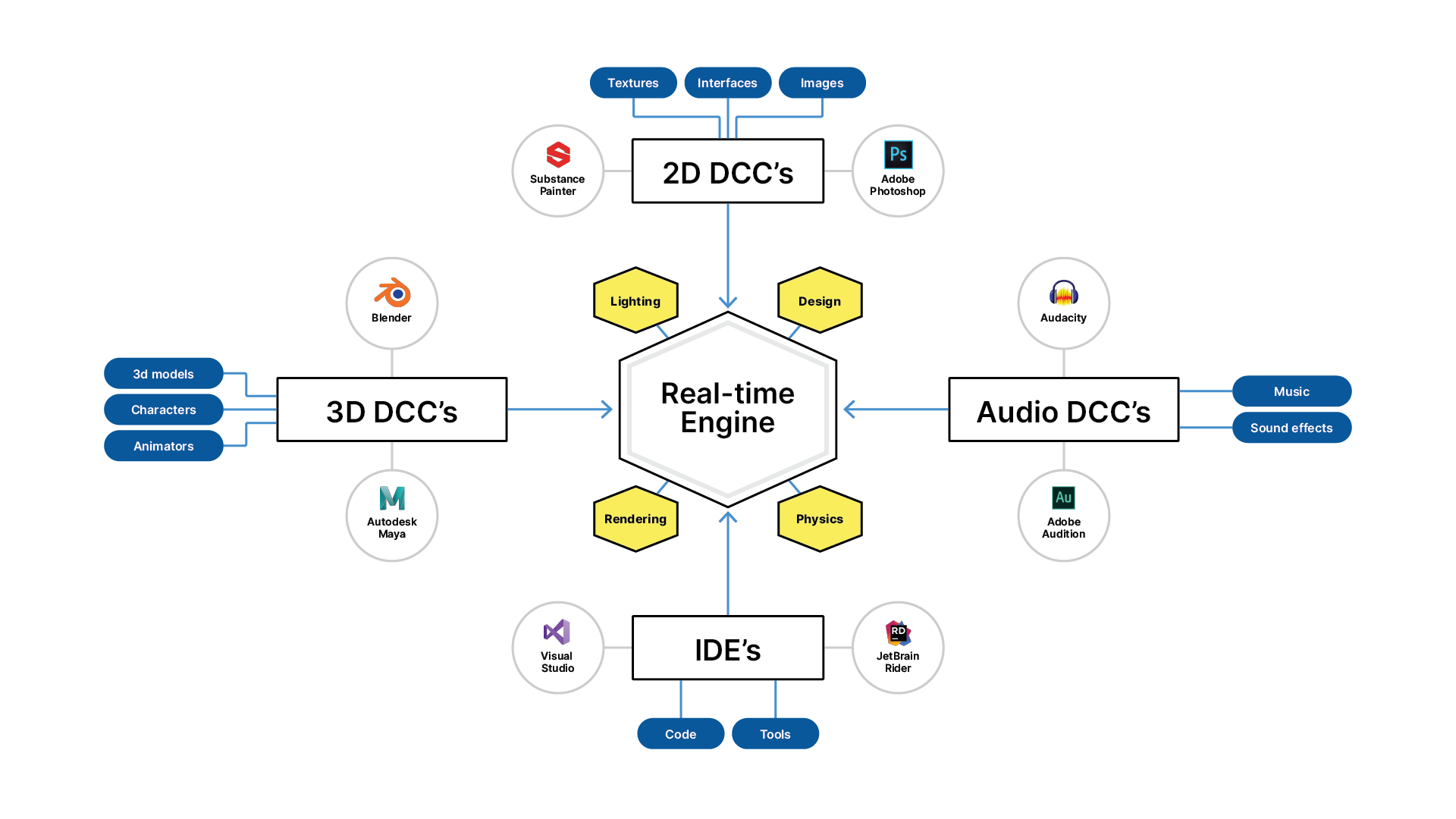

Inside a game engine, you don’t create assets — the objects and sounds that are the building blocks of the interactive experience. Instead, assets are created in specialized external programs called Digital Content Creation (DCC) tools. Many DCCs are integrated with Unity to ease the process of importing them.

The most common types of DCC tools used in real-time development include:

- 3D DCCs are programs for creating 3D models, animated characters, and environments; examples: Maya, ZBrush, and Blender.

- 2D DCCs: programs for creating 2D images, illustrations, textures, and interfaces; examples: Photoshop, Illustrator, Substance Painter, and Gimp.

- Audio DCCs: programs for recording, editing, and mixing sound effects and music; examples: Audition, Logic Pro, Reaper, and Audacity.

- Integrated Development Environments (IDEs): programs for writing code in a variety of languages; examples: Visual Studio and Rider

- Real-time Engines: programs for real-time development, rendering, and publishing of 3D content or applications; examples: Unity and Unreal

In upcoming tutorials, we’ll describe each type of DCCs in detail.

Unity Asset Store

Good news: although learning to use a DCC to create Unity assets can be an excellent skill to have, you don’t have to build every asset in your projects from scratch. Hundreds of ready-to-use assets created with DCCs are available to you through the Unity Asset Store. Some of them are even free. You can download and import assets directly into your own projects using a link between the Asset Store web site and the Package Manager in the Unity Editor, via your Unity ID. In the upcoming tutorials, you’ll go to the Asset Store to get specific assets to enhance your projects, and you’ll be ready to explore the Asset Store on your own.

5. The Unity Story

It started with a game

The first product ever released by Unity Technologies was not a game engine, but a game.

In 2005, Unity’s founders, Joachim Ante, David Helgason, and Nicholas Francis, released the video game GooBall for MacOS, a year after the formation of their company, which was then called Over the Edge Entertainment. The game was created with an engine that they built from scratch, with the intention of licensing the engine to other developers.

How games were built (before Unity)

Most game companies at the time created their own in-house engines for their various projects, sometimes even building a new one for each game they created. This let them create a suite of tools that met their specific needs, but at the cost of a great deal of time and money. While development on a game could often occur in parallel with engine production, any core changes to the game’s concept might end up requiring a rework of the engine as well, which meant that it would take longer to release a sellable product.

The limited availability of pre-built engines was especially problematic for independent developers, as individuals and in small teams. Game engine creation is an extremely technical process, and requires extensive programming experience. Unless an independent developer had extensive programming experience, they would have no choice but to license an engine, which was often cost prohibitive. For these reasons, prior to the mid 2000s, independent game development was far less common than its corporate counterpart, and commercially successful independent games were rare.

Birth of an engine

GooBall wasn’t a success, but Unity would be. Ante, Francis, and Helgason premiered the Unity engine at Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference. Initial adoption of the engine was slow but would soon catch on with indie developers.

Unity hit the market in the mid-2000s, when the face of the game industry was beginning to change. Unity was uniquely positioned to be an important part of the “indie game revolution,” as it would come to be called. Three factors were critical to Unity’s early success: the introduction of dependable digital distribution models for games, a focus on appealing to independent developers, and support for early smartphones.

The adoption of high-speed internet was in full swing when Unity first launched, which made digital distribution of games a viable option for the first time ever. Before then, indie developers had very few choices in distribution models for games. Nearly all games were sold in retail stores, through arrangements with major publishers — the very groups that indie developers were “independent” from. With faster and more readily available access to the internet, the average user could easily download games hosted on a developer’s personal website, or through online storefronts called digital distribution services which began emerging during this time. These services manage hosting, sales processing, occasionally digital rights management, and often a social component as well. By using one of these services, developers became able to spend more time creating and maintaining their games instead of managing sales and distribution. While retail game sales still made up the majority of game purchases in the mid-2000s, a growing number of consumers began adopting this new way to find and play games. Suddenly, indie developers had access to their audience.

When Unity first launched, it differentiated itself from other licensed engines by offering pricing that was affordable to independent developers. Unity also focused on providing a good experience for developers — something that most other licensed engines overlooked. These two factors helped Unity gain traction in the growing indie development community.

When the original iPhone opened up the App Store to third-party applications, Unity was one of the first tools to support the platform, which solidified its role in the exploding mobile games market. Soon, more than half of the games on the App Store were developed with Unity — a trend that continues today for mobile games on both iOS and Android.

6. Next steps

Unity's core value was once to “democratize game development;” today it is simply to “democratize development” — not to move its focus away from games, but to open the doors to so much more. Unity has now evolved from a game engine to a real-time engine, adding new capabilities that serve game developers as well as animators, engineers, designers, trainers, and marketers across many industries. Unity is for everyone, and everyone is welcome.

Now that you know the Unity backstory, continue to the next tutorial to find out about the many industries that use Unity’s real-time engine.