Choose and craft your concept

Tutorial

intermediate

+10XP

30 mins

10

Unity Technologies

In this tutorial, you’ll choose a basic idea for your game and craft it into a more detailed concept.

1. Overview

The first stage of the game pre-production process is choosing and exploring an idea for your game. This is split across two tutorials: first you’ll choose and craft an initial concept, and then you’ll refine that concept by considering your target players more deeply.

In this tutorial, you will:

- Select an idea to develop into a game.

- Reflect on inclusive design in concept development.

- Evaluate your concept and what is represented in it so that you can work towards creating more inclusive experiences.

2. What sort of game experience do you want to create?

There are different types of initial ideas that can be the starting point for a game. You could start with an idea for:

- A specific game type and genre that you’d like to explore — for example, “I want to create a first person adventure game based on the classic hero’s journey.”

- A specific mechanic or system that you want to center in your game — for example, “I want to create a roguelite based on repeated descents into an underworld and how that might change you.”

- An idea for a narrative that you’d like to shape a game experience around — for example, “I want to create a game that’s about finding community when you move to a new and unfamiliar place.”

- A question that you’d like your player to explore through your game — for example, “I want to create a time loop experience that explicitly asks players what it means to achieve a perfect ending.”

- Something that you’d like to build a game around that isn’t quite covered by the other options — for example, “I want to turn feeding my pet cats into a resource management simulation game, because that idea delights me!”

An initial idea, whatever its form, will be at the heart of your concept.

3. Case study: Our initial idea for Out of Circulation

In this course, we’ll break down how we approached creating Out of Circulation as an example to help you think about your own game. It can be helpful to think about our vertical slice in two different ways: it’s a section of a game, but it’s also a tool to help you learn more about accessibility in games.

The requirements that we defined for Out of Circulation as a tool to support this course had a significant impact on the game idea that we chose.

Learning experience requirements

Practical design and development work, both in-engine and out of it, is at the heart of this course. We wanted to create a vertical slice of a game that was as accessible as we could make it, but that also had room for you to adapt and extend the example yourself.

We also knew that we wanted to work with the following high impact areas of game accessibility in detail:

- Control remapping

- Text size

- Use of color

- Subtitle/caption presentation

The game idea

We spent some time discussing these course requirements and the different types of game that could support them best. Although the more detailed scoping came later, we also decided at the very beginning of the process that multiplayer functionality was out of scope for this project.

A point-and-click narrative adventure game felt like an excellent fit for our requirements. This type of game also had the benefit of having functional similarities to other types of interactive experiences that intermediate creators might want to make, such as architectural simulations and product demos.

4. Choose an idea to work on

Take some time now to choose one or two initial ideas that you’re interested in using for this course. Two ideas is helpful because it means that you will have a back-up if you decide to restart with a new idea during the planning process.

You might already have a clear idea of what you want to work on — that’s great! If you don't have an idea yet, read on for some suggestions and guidance on their relative levels of challenge for an intermediate creator.

Lower challenge options

Single mechanic games are good options if you want to make a more accessible game without a lot of system complexity. Simple elegance is also a design challenge in itself!

Examples of this type of game include:

- Matching: The player matches simple cards in a deck and attempts to match them all.

- Movement: The player moves or rotates shapes into the correct position.

- Resource allocation: The player receives information and uses that information to assign resources to different pools

- Time constraints: The player must complete a set of actions within a specific timeframe.

Higher challenge options

If you want to try a more challenging game idea, you can choose a game that:

- Includes more complex systems, for example an inventory system that the player will manage via a user interface.

- Gives the player more freedom, for example a first person walking simulator or exploration game where the player can move between spaces and interact with objects with more agency.

Customize the challenge with a focus area

Later in this project, you’ll define and prioritize accessibility requirements for your game. When you do this, you can focus on the accessibility of one particular aspect of your game in detail. This is another way to customize the level of challenge until it feels right for you.

For example, imagine that you want to make a hovercraft flying simulator game. When you plan the game, you might decide to focus on making that hovercraft respond to remappable player input as your top priority and spend less time working on other elements in the game.

5. Inclusive design for concept development

You may find it helpful to develop your idea into a more detailed concept at this stage, especially if your game is narrative-led or requires important worldbuilding.

As you develop your concept, it’s critical to reflect on the things that you are planning to include in your game, including people, events, objects, and perspectives. Earlier in this course, you considered the negative impact of assumptions. Keep this in mind when you develop your game concept — representing people’s lived experience thoughtfully and respectfully in your game is an important aspect of inclusive design.

What does this mean in practice?

Think carefully about the perspectives that you are adding as a creator and consider whether the particular story that you want to explore is yours to tell, especially if you are writing outside of your lived experience. As with other areas of design and development, feedback from people who have lived experience of — or related to — the story that you are portraying is an important tool to support an inclusive design approach.

The International Game Developers Association (IGDA)’s 2022 Inclusive Game Design and Development paper includes a detailed overview of inclusive design and development considerations that you can refer to as you develop your concept.

6. Case study: Out of Circulation concept development

During pre-production for Out of Circulation, the case study for this course, we developed a range of initial concepts and refined them using feedback from potential players. Narrative, characters and worldbuilding are integral parts of a narrative adventure game, so this was an important part of concept development. If you’re developing a different sort of game idea, you might want to leave this review process for now. You can return to it when you gather feedback on your game visuals and overall design.

The process that you take to develop your context will depend on your personal preferences and the sort of game that you are making. We developed the concept for Out of Circulation in three stages:

- Creative exploration

- Focused concepts

- Feedback and refinement

Stage 1: Creative exploration

First, we explored a number of possible themes. Out of Circulation needed a theme that would be engaging and suitable for a wide audience. Our vertical slice also needed to be based in a small set of related locations that were geographically close.

We explored a range of narrative and visual theme options, including:

- Folklore-influenced fantasy.

- Film noir pastiche.

- Aquatic urban fantasy.

- The adventures of Sir Pugknight, a pug who is also a knight errant.

For each option, we paired art and narrative concepts to help the team evaluate the potential of each idea. Our goal wasn’t to create something polished, but to define enough of a look and feel that we could evaluate each theme for the game.

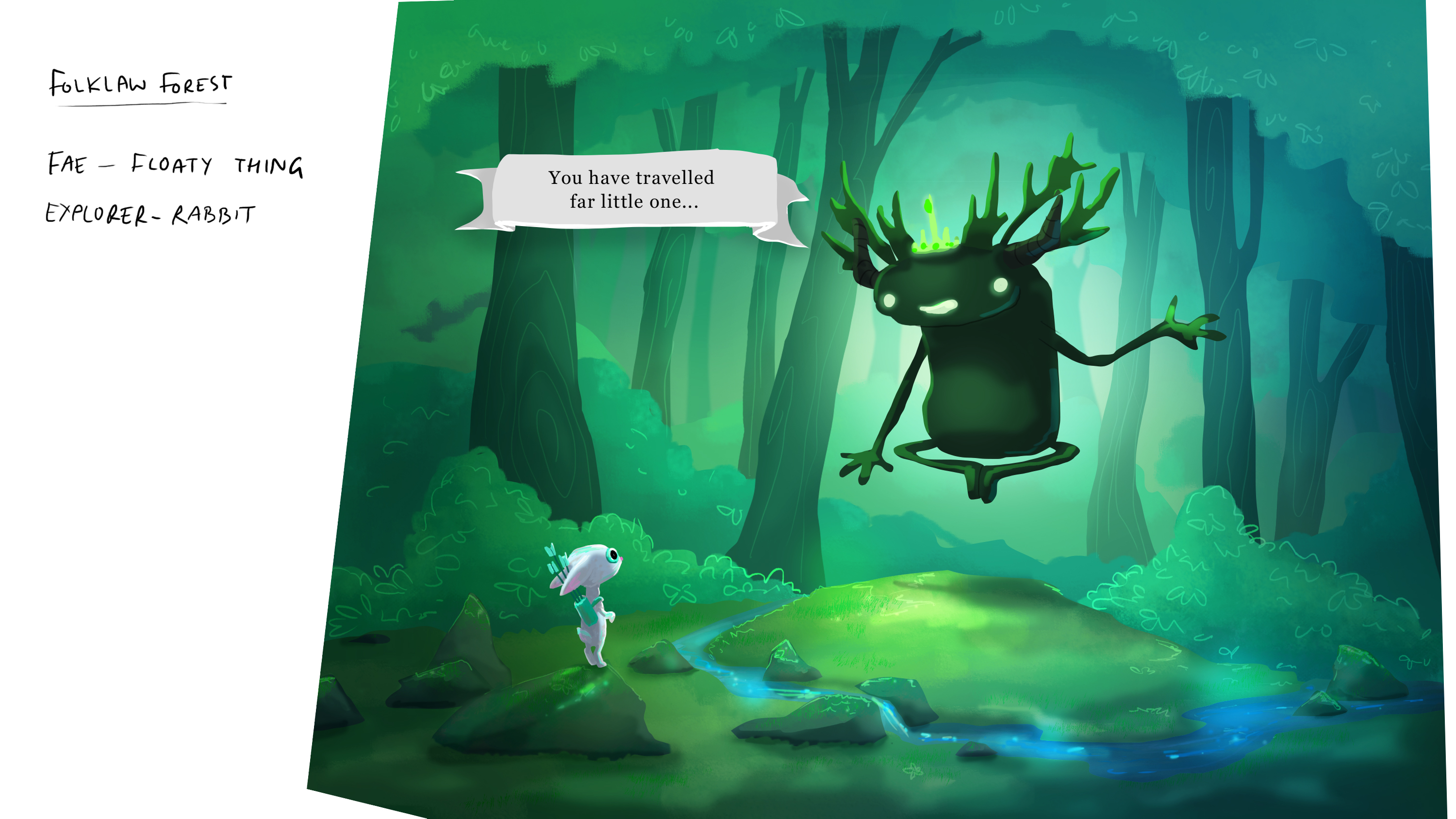

Here are the paired concepts for the fantasy theme, for example:

"Something strange is happening in the wildlands. Folk fall asleep without rhyme or reason: unharmed, or so it seems, but dreaming further away than they can be called from. Quartz is no stranger to the forest; they’ve traversed its friendly glades and outer edges since they were young. But to find answers for their community, and wake their slumbering friends, they’ll need to journey further than they ever have before."

At the end of this initial exploration stage, we chose two themes to progress for further review: the urban fantasy and film noir themes. We felt that our concepts for these themes offered the best location options for the vertical slice, and they also had fun visual possibilities that we could explore.

Stage 2: Focused concepts

For each of our chosen themes, we then put together a more comprehensive overview of our proposed approach. This overview included:

- Different visual style options.

- Slightly more polished narrative overviews.

- High level details about the characters and adventure plot.

- Notes on how the team would approach the theme.

Here is an example of character design concepts for the urban fantasy theme:

The aim here was not to lock in details early in the process, but to give reviewers enough information about our intended approach that they could provide helpful feedback.

Stage 3: Feedback and refinement

Next, we asked a group of colleagues with a diverse range of lived experiences to review the theme concepts and provide us with feedback.

The feedback that they provided on each concept was invaluable — it helped us to consider each concept with fresh perspectives and identify that the urban fantasy theme was clearly the best one for this project. Our example vertical slice needed to appeal to a wide audience; film noir tropes, however playfully used, could exclude some potential learners.

7. Connect with others to get feedback on your concept

You don’t need to put together a full concept review pack to get feedback on your idea for your game — it can be as simple as sharing a brief overview of your ideas with a few people who are willing to give you their opinion. Feedback at this early stage is a very helpful tool to make sure that you are on the right path.

If you’re struggling to find someone to give feedback at this stage, you could:

- Ask other creators you know for focused feedback on an idea and offer to support them in kind. This can be useful even if they are not fellow game creators, particularly if you’re asking about high level concept ideas.

- Engage a specialist consultant to provide feedback on your idea and concept before committing to development.

- Reach out respectfully to contacts on social media or in community groups and ask them if they would be willing to give you some focused feedback on your concept. Be mindful of the time commitment and be aware that they may not be able to support this request.

Note: This concept feedback is not the same as connecting with user testers for your game, which you’ll explore later in this project.

8. Next steps

Now you’ve chosen a high level idea for your game, you’re ready to refine it. In the next tutorial, you’ll focus on learning more about your target players for the game. You’ll also create a tool to help you prioritize their needs during design and development.