Designing for impact

Tutorial

·

Beginner

·

+10XP

·

15 mins

·

(74)

Unity Technologies

When designing for impact learn how to align the actions of the player with the impact you hope to create.

1. Introduction

For experienced game designers, the material in this chapter should feel familiar, but also new. For example you might find yourself imagining a slightly different method of playtesting than you are accustomed to, or rethinking how you conceptualize a game loop.

For researchers or activists, parts of this chapter will also feel familiar, and will probably feel very basic or remedial. That’s OK. Making a game that involves both subject matter experts and game designers means taking a journey together, with each party on both familiar and unfamiliar ground.

As you go through this chapter, frequently refer back to the cheat:

Align the actions of the player with the impact you hope to create.

2. Matching game mechanics to action

“Mechanics” is probably the most overused word in game design, and two designers rarely agree on exactly what the word even means. Here’s a useful working definition:

- “Mechanics” describes the various activities, or verbs, that the player can do and take within a game.

3. Be descriptive of action

Games are built upon actions. In fact, this is what distinguishes games from other types of media. Action movies are cool, but it’s very different to watch an actor perform actions, versus performing those actions yourself as a game’s player. Starting with the question, “What does the player do?” is a strong way of grounding yourself throughout the process of game design.

Exercise: Close your eyes and imagine for a moment what the player will be doing while they play your game. This may be more than one thing, but imagine as much as you can.

Pausing to perform this exercise can be extremely helpful at any point, but it is particularly useful in the early stages of game design.

4. Impact is also action

Regardless of the topic of your game for impact, the impact that you intend it to have can probably be articulated as “action” as well. Sometimes the action is specific and guided, such as with a citizen science game. Sometimes it’s more general, like, “learn a method or skill” or “raise awareness.” In any case, using the action nature of games in service of your impact goal can be very powerful!

5. Goal + mechanics = opportunity

Your characterizing goal plus your vision of the gameplay mechanics can work together!

In This War of Mine, a remarkable game about a very serious topic, the developers intended to make a game about the experience of civilians in a war zone. This could be described as their characterizing goal. The many design decisions that followed, defining the player’s actions and decisions, were then driven forward by this goal.

Consider the information a player of This War of Mine must assess and the risk vs reward calculations they must make before they venture out of their house to gather food and supplies:

- The state of supplies in the house is the signifier (what the player hears or sees).

- The decision to go out for supplies is the mechanic.

- The results of the expedition (more supplies vs injury/death) is the feedback.

The game Working with Water has a clear characterizing goal: “to simulate the challenges of water management for the growing population of the Central Coast [of Australia],” which was provided by the developer’s client, the Australian Central Coast Council. The mechanics of this simulation game are driven by the game’s goal: to communicate the water conservation needs and challenges of the region in a deep and immersive way.

Dumb Ways to Die is a game that was created as part of a 2012 campaign emphasizing safety around railroads in Australia. The game accompanied a very funny video and song, and was part of a multimedia campaign that became a viral hit. The game, created for mobile devices, is a collection of small, quick minigames, some of which are unrelated to the theme, and some of which are closely related. For example, one of the minigames has the player connect the strings of helium balloons to a hand, and upon success the character avoids chasing the balloon off the train platform. This message (hold on to your stuff, or if you drop it, don’t chase it) is united with the game’s mechanic in a clever, memorable way.

6. Extract verbs from your goal

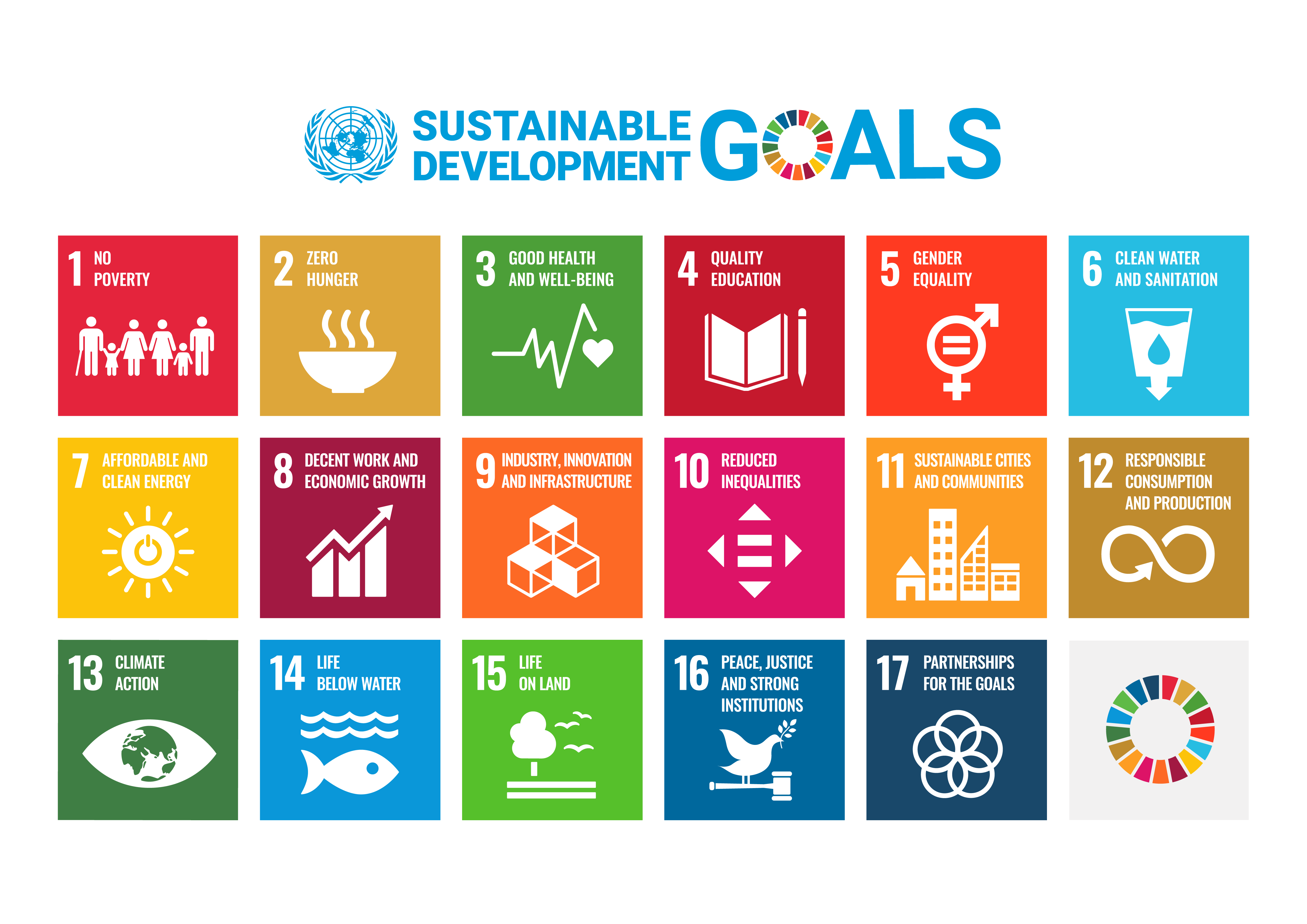

Your project should have an impact goal, like the UN’s “Sustainable Development Goals” that can be found here. By considering this impact goal in terms of the action that a person would take, you can extract verbs from that goal, with the target of eventually matching that verb with game mechanics.

Let’s say for instance that a game’s goal is to create a simulation challenge for creating a carbon credit economy. A common way of accounting for carbon credits is to purchase and set aside forested land to preserve its carbon sequestration function. The player would then have a few verbs to actualize that process:

- Draw: To section off areas to be preserved.

- Bid: To make an auction offer on the land.

- Hire: To hire workers to ensure the land remains preserved.

You might already be thinking about some of the possibilities for “what does the player do?” in terms of interface and input.

Let’s take “Bid” as an example:

- The player sees their current budget/cash as a textual signifier.

- Computer controlled NPCs competitively bid, and the player sees these numbers as well (more signifiers).

- The player selects their final bid amount and submits it (the action).

- The game gives the player clear feedback regarding whether the auction is won or lost.

7. This is it! This is the trick!

Rather than starting with the game itself, you can begin by thinking through what the actions are that the game is about, and once you’ve articulated that, you can generate a set of game mechanics that reflect those actions. Chances are, an interesting game will emerge!

This marriage between mechanics and impact goals is the magic trick to making an interesting, hopefully effective, game for impact. If you only remember one thing from this guide, we hope that this is it!

Extra credit: Watch videos from Game Maker’s Toolkit, a YouTube series by Mark Brown, that breaks down game design decisions in popular games – one of the best ways to learn what works. Watch a few to understand how to play games critically yourself.